It’s good to go to conferences where you don’t know many people. Expand your orbit, expand your mind. I knew just two people on the agenda of the recent ‘International School Choice and Reform Conference’ (4-7 January, Madrid) – both from the US. One was an academic hero of mine whom I’d never met before: Eric Hanushek, who did pioneering work on the empirical links between learning outcomes and economic growth. More on Eric later. The other, I played rugby with over 30 years ago in England. He used to throw the ball (quarter-back style) the entire width of the rugby field, straight into the hands of our speedy winger. Noone ever expected it and it worked a treat.

The ISCRC is an annual conference of just under 200 academics, government officials, policy wonks and practitioners – mostly from the US and Canada, with a few from Europe. It focuses on ‘school choice’ and ‘educational freedoms’ as organising principles, and includes people working on Charter Schools, home schooling, independent schools and government regulation. I went to the conference to see whether and how GSF – and by extension our members in low- and middle-income countries (LICs & MICs) – might share some alignment with the large ‘school choice’ movement in the US, and to see if there are opportunities for learning and collaboration. Here are my take-aways:

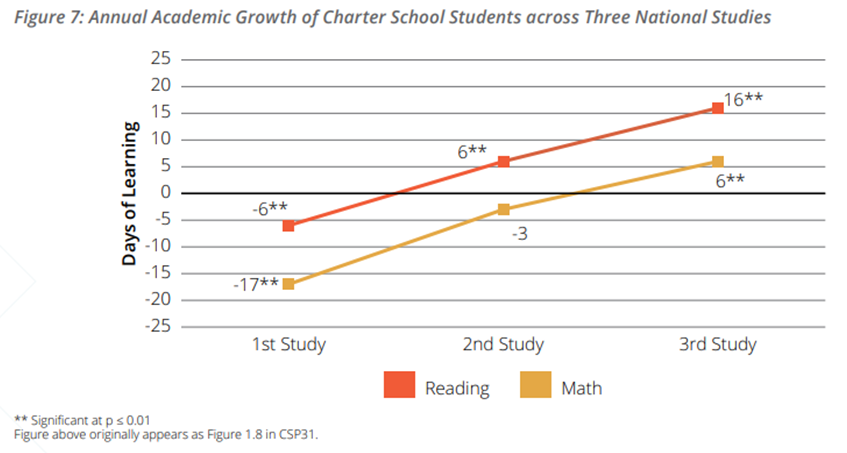

- Charter Schools are out-performing traditional public schools in the US, and ‘educational freedoms’ seem to be positively correlated with learning outcomes. A new 2023 study across 23 states finds a learning premium of 16 additional schools days for reading (benchmarked against a 180 school day year), and 6 for maths, when comparing Charter Schools with traditional public schools. Progress is highest for Black, Hispanic & low-income communities, and is driven by Charter Management Organisations (chains of Charter Schools, which average around 16 schools per CMO) rather than single Charter Schools. CMOs show learning gains of 27 days for reading and 23 for maths. Also noteworthy is that this is the third round of the same study which has been conducted in 2009, 2013 and now 2023. It has shown a clear upward trajectory in the performance of Charter Schools relative to traditional public schools (see below), i.e. they have taken time to succeed.

More broadly, there is some evidence that ‘educational freedoms’ in the US (not just Charter Schools) are positively correlated with learning outcomes.

- There is a large infrastructure (people, institutions, research, legal tools, practitioner tools, funding…) supporting educational freedoms in the US, and to some degree Europe: LICs & MICs need to grow this infrastructure at the country and regional levels, if educational freedoms are to be protected and optimised for better learning outcomes for children. This applies to the global level too, where there is little-to-no representation of the non-state sector in global education governance, in spite of it providing over one quarter of basic education services globally (and rising).

- Education freedoms have been established and sustained in the US through a combination of social movements and (bi-partisan) political support. One academic at the conference observed that there have been two distinct shifts in the social and political environment in the US: first, independent and charter schools breaking state monopolies of provision; and second, ‘parental choice’ now as the strongest driver of educational freedoms, in large part driven by parents in the powerful school choice and home schooling movements. Though political support for school choice is leaning to the right in the US, I’m told, there are also Democrat legislatures that are supportive, particularly for voucher schemes. I’m reminded of the UK, where Academy schools (publicly-funded, fee-free and privately-run) were an invention of the Labour party (political left), before their expansion and re-definition by successive Conservative governments (political right). Noone owns educational freedoms politically, and that’s the way it should be.

- The new vogue in financing is Education Savings Accounts: now in around 13 US states, ESAs transfer education funding to parents to redeem that funding against approved educational providers of their choice. They’re like traditional voucher schemes when they’re used to redeem the ESA against a single provider/school (which is the case in 72% of ESA usage), but they’re more radical when used in an à la carte way (28% of ESA usage), i.e. picking different providers for different subjects and activities. I’m not sure ESAs (the à la carte version) would work in lower-income countries. There would be difficulties on the demand side (information for parents, particularly illiterate parents), on the supply-side (diversity, quality and scale of service providers) and on the administrative and regulatory sides (hard to administer? hard to oversee?).

- They say never meet your heroes, but my hero was fabulous. I did meet Eric Hanushek – a wonderfully wise and modest man. He’s still exploring the empirical links between learning outcomes and economic growth. His latest estimate is that the economic gains from universalising literacy and numeracy globally would be around $700 trillion US dollars – an unfathomable figure; five times current global economic output – with the big winners being sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. It’s hard to think of anything more transformational.

I think non-state actors have a critical role to play in working towards that transformation. At GSF, we don’t believe that private is better than public, nor that there should be more private schools. We believe that the non-state sector can complement and support government provision of basic education, and also bring new ideas, funding and energy to the sector. It is also important to note that international human rights law specifically protects the liberty of parents to choose schools other than Government schools for their children.

But we do see educational freedoms under threat in the global education architecture. Led by five organisations with long-standing campaigns against the private sector, the Abidjan Principles have invented a range of prohibitions and constraints on private sector participation, with no basis in international human rights law. Ongoing work on the evolving right-to-education is proposing ever-tighter restrictions on private operators, including prohibiting state support to any education provider charging fees.

I think our alignment with the US movement for ‘educational freedoms’ is two-fold: (i) to figure out how the non-state sector can deliver good education outcomes at containable costs, and without driving stratification and inequality in the broader education systems in which they sit, and (ii) to protect the operating space for private providers, through elevating parental voice, building tools and institutions, and supporting enabling legal and regulatory environments for non-state actors. According to UNESCO, Governments financially support non-state schools in 171 out of 204 countries, including private schools in 115 countries. Let’s not close down these choices made by Governments and by parents. Let’s help schools (delivery) and Governments (contracting and oversight) to do it better. We need all hands on deck to meet global education goals.